He moved glacially slow. The robin, intent on finding bugs, seemed unconcerned, perhaps even unaware. As the boy narrowed quietly in on his target, he suddenly reached out and grabbed the bird's feathers. Success! Only the bird started flapping it's wings and chirping and protesting shrilly! The boy didn't have a plan for after he caught the bird, and suddenly wondered why he had wanted to catch it in the first place. He let go and the robin flew far away.

The boy was myself, in the yard at the side of what we called the "Big White House," in Spirit Lake, Idaho. It was the third place that my family had occupied in Spirit Lake, since moving there shortly after I was born. The first was a lake cabin at Sedlmayers' Resort. I only have a few memories from that time; my father fishing for rainbow trout on the ice, and cooking them on the shore; my older sisters forcing me out into the rain during a lightning storm; my father whittling me a toy, which at first looked like a gun, but ended up being a car. I also remember my brother falling into the icy cold water and being immediately pulled out, but others say it was me.

We moved from there to the more downscale Conklin's Resort, into a shabby two room cabin. My father stapled plastic around the porch to make an enclosed room for my older sisters. My younger sister Marisa was born while we lived there. We picked her and my mother up from Dr. Fredrickson at the small, pale green Spirit Lake hospital. Marisa was tiny and wrapped in a blue blanket. The addition of a fifth child motivated my grandmother to step in and rescue us. She purchased the Big White House, which had two floors and a basement, multiple bedrooms and a garage. Our now sprawling family moved in immediately.

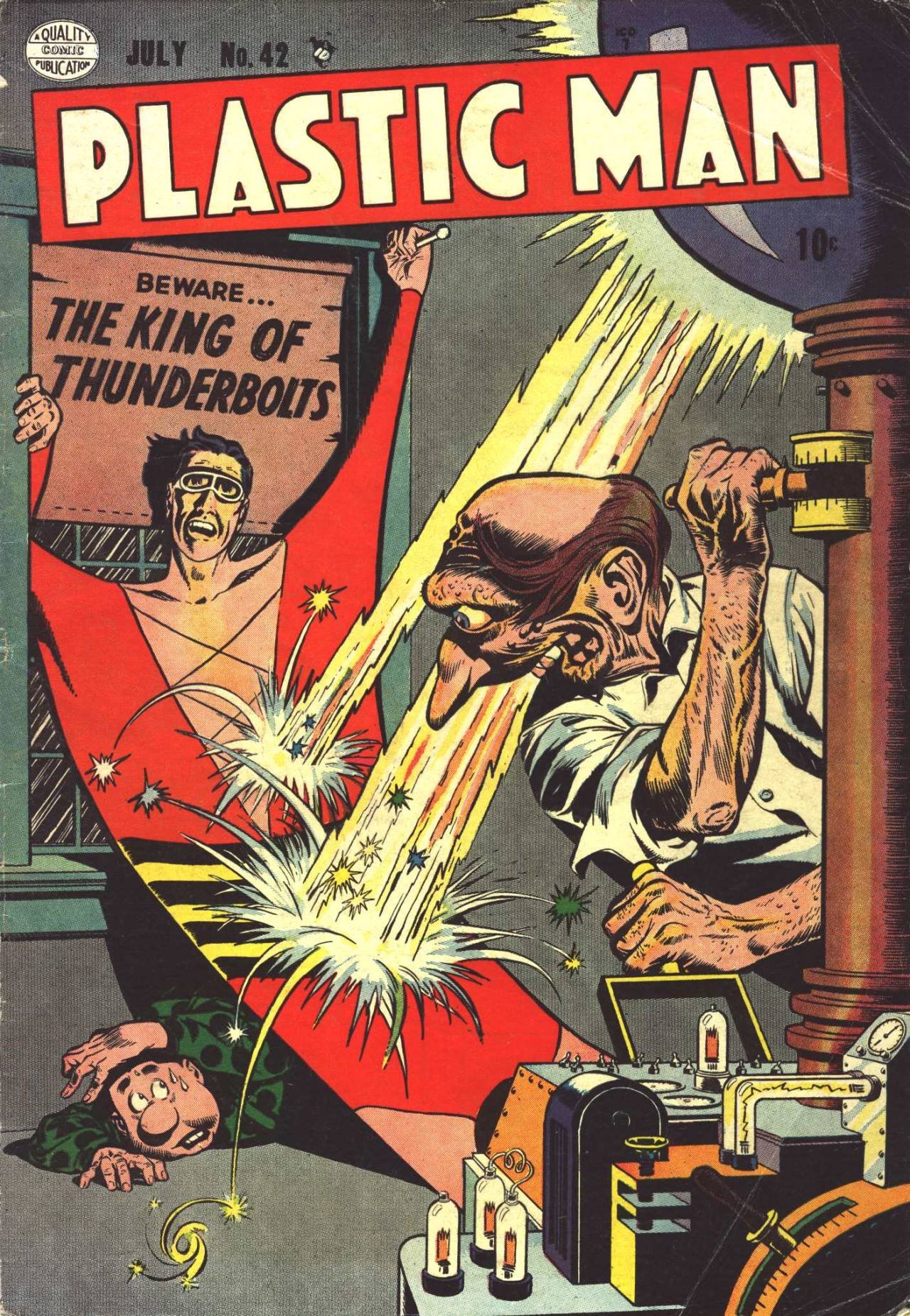

I taught myself to read when I was three. I don't recall doing this, I just remember my mother's surprise when she realized I was reading. It opened a Pandora's box of new experiences, one that I have yet to close. I had a stack of comic books next to my bed, with current favorites rotating to the top. I remember Plastic Man, Dick Tracy and Mutt & Jeff. My parents also had a vintage copy of The Golden Book of Fairy Tales, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham. My brother and I were fascinated by Rackham's naked and nearly pubescent figures, and we gave them all cunts using strategically placed pencil marks.

I caught chickenpox at some time during our stay there. I was forbidden from scratching the sores, which itched like the devil. I spent the entire time running around stark naked, up and down the stairs, around and around in circles in the living room, and through the hallway to the kitchen. The sores spread down my throat, and I could only get relief by sucking air between my tonsils, making grunting noises like a sow. It passed eventually, but I still recall the coloring book that I scribbled in during my recovery; The Last of the Mohicans.

There was an elderly couple living next to us, the Alexanders. The affable Mr. Alexander would give me his extra Bull Durham pouches and leftover rolling papers, which I would fill full of dirt, and roll dirt cigarettes. I also learned to make five o'clock shadow with coffee grounds, and by accident discovered that by pressing the cat against a jam covered torso you could appear as if you had a hairy chest and an extra Y chromosome. I would lurk around like this, wearing a wife beater t-shirt, a dirt cigarette hanging out of my mouth and, frequently, a pocket full of earthworms. Such things as dreams are made of.

Across the railroad tracks west of the Alexanders' house was a system of crumbling concrete foundations. We were told it was an abandoned military installation. All of the kids in the neighborhood would play amongst those ruins, occasionally stumbling over a salt lick that had been left for the deer. We'd often find black widow spiders hiding amongst the rubble, but we didn't pay them much heed. There was a very poor family that lived a block away from us that had a half dozen boys, the Bakey boys we called them. The one closest in age to me was named Arnold. He may have been the youngest. One of the older Bakey boys was the first to grow pubic hair, and he pulled his pants down just far enough to show us. We couldn't wait for ours to fill in. No matter what we were up to, there was one ritual that was practiced without fail. When we heard a train coming, everyone would race to the tracks and wave to the conductor, and watch until the train disappeared around the bend. When I hear or see trains now, I'm overcome with nostalgia.

There were two competing grocery stores at the top of the hill on Main Street. One was called Sippert's, and was where my mother shopped. One day Bobby, Marisa and I got the idea to charge cookies to our parents' account, then retreat to our "fort" with our booty. The fort was just a tangle of bushes, but shielded us from the main street. After executing this caper a couple of times, Mr. Sippert became suspicious and informed our parents, putting an end to our scam.

My older teenaged sisters, Marilyn and Marcia, were always fighting, over boys, clothes, whatever. Marcia could be especially vicious, throwing lit matches at Marilyn. Marcia had a string of ne'er-do-well boyfriends, and they'd make me smoke cigarettes or torture me in other ways. Once they both had an older boyfriend that was on the run from the local sheriff, who was a skinny guy with a pencil thin mustache named Bud Walkup. My sisters hid the fugitive at our house for a couple of days, while my mother worked and my father was away on business. They told me that if their friend was caught "they'd put him in the jug," which I took literally, trying to imagine how they'd get him in one.

During this time my mother worked at Sedylmayer's, which had a restaurant and soda fountain, a dance floor with a jukebox that played Patsy Cline, Hank Williams and Brenda Lee, along with a dozen or more cabins, docks, canoes and water-bikes that they'd rent to vacationing tourists. My father had a truck stop diner in Rathdrum, then worked nightshift at another truck stop, and for a period drove the hills and highways as a traveling salesman, in a succession of unsatisfying employments. He had a pilot's license and had been a deejay for the army at the tail end of World War II. He may have had ambitions but they didn't survive the sudden responsibility of raising five children. He once told me that the important thing was to "get by."

Across the street from the Big White House was Mrs. Spooner's an old woman with a bottomless cookie jar. She lived in a quaint looking stone house. An alleyway ran alongside the south side of it, and one day as Bobby and I were playing there we disturbed an hornet's nest. One minute we were laughing, the next we were crying and running our asses off. My mother counted over 50 stings on my back, but Bobby got the worst of it. A hornet had crawled inside his nose and stung him there. His lips began to swell, then his cheeks. His eyes followed and finally his whole head swelled up like a balloon. He was trotted over to the Alexander's to show off his grotesque countenance, the progress of which had already been documented in stages with my dad's camera.

My brother and I didn't play together all that often. There was always some tension that I couldn't put my finger on. It never occurred to me that I had usurped his favored status rather abruptly, having been born a mere 10 months after he was. It was an underlying tension that persisted our entire lives, until he died of kidney disease at age 50. He had a dogged personality. I remember when he learned to ride a bicycle, by coasting down the alley toward the Alexander's garage and crashing into their woodpile in order to stop. He did it over and over, crashing every time, until he could ride. Watching his hard lesson put me off learning to peddle a bike until I was ten.

I was drawing all of the time, copying characters from my comic books, and making stuffed alligators out of paper, scotch tape and Kleenex. I cannot remember a time throughout my childhood when I was not drawing. My parents, in their naïveté, just assumed that I'd be an artist when I grew up, and encouraged me in that direction. Their simple faith in the rewards due talent can be forgiven, I guess. They had grown up during the Golden Age of Illustration, before cameras and color film knocked the supports from underneath the market. Successful art careers greeted them from the covers of the Saturday Evening Post, Harper's Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, Weird Tales and other magazines that populated the stand at the local drug store.

I went to my first year of grade school in Spirit Lake, in a large, two story brick building. I recall very little about it, except on one occasion getting into a fight with my brother on the playground, and spraining a knuckle on his skull. I would walk to school zig-zagging through the streets, and traversing the town park, a two block long affair with a stone fountain and pond in the middle. It was known that the little kids would piss in the pond, and one time a group of older boys pushed me into it. Humiliated, I pulled myself out and ran home, suddenly realizing that children could be treacherously cruel.

After one year of Spirit Lake Elementary my parents decided to move to Spokane. I was through with Spirit Lake, or at least I thought I was.